Documents relevant to the use of medicines were also reviewed.

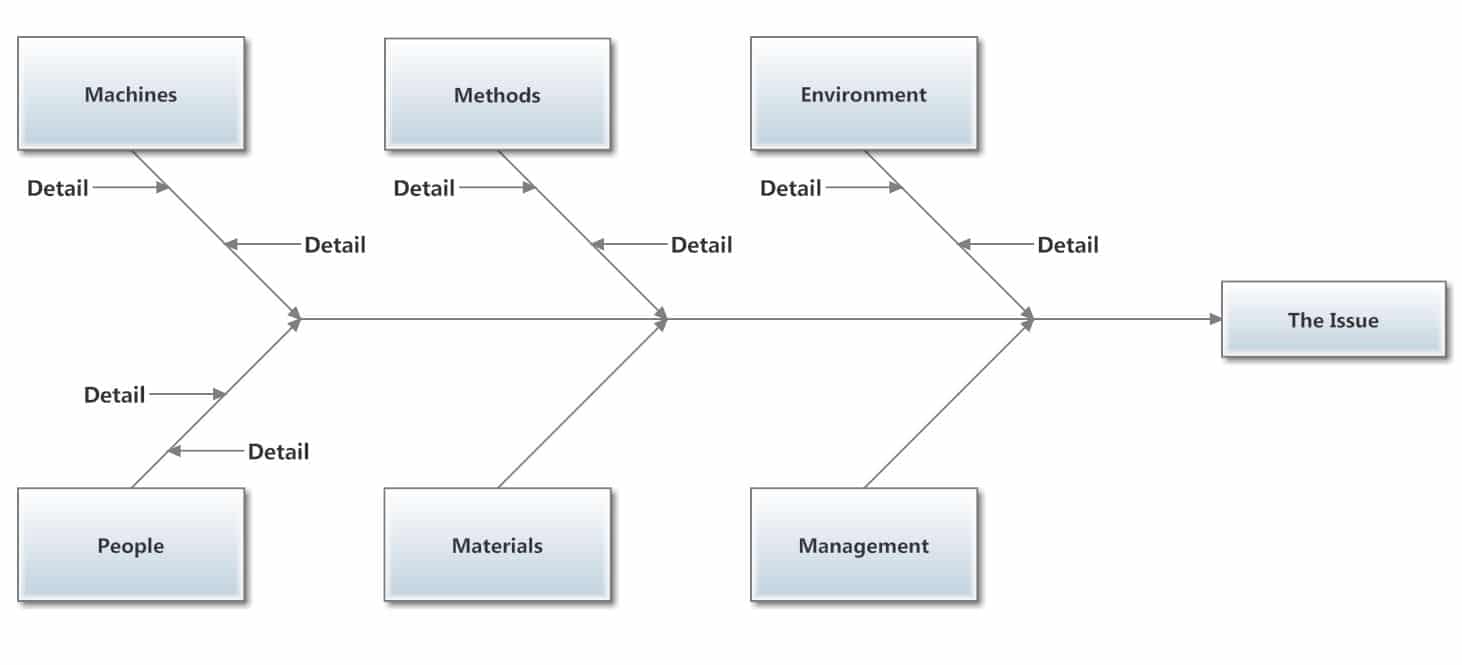

#Ishikawa diagram healthcare professional

Interviews were conducted with local partners and stakeholders such as representatives from the MoH, professional organizations, pharmaceutical administration authorities, reproductive and maternal health non–governmental organizations (NGOs). For each country, a collaborative team of researchers from WHO, UNFPA, the Ministry of Health (MoH), and local representatives conducted site visits. The data in each country report consisted of observations, interviews and archival analysis. We also collected information pertaining to the availability of calcium gluconate – the recommended antidote for MgSO 4 toxicity – whenever the relevant data were reported. In this study, we focused on three medicines – oxytocin, ergometrine, and MgSO 4 – for which data were available and consistently reported for all seven countries. These medicines included: oxytocin and ergometrine injections for prevention and treatment of PPH MgSO 4 injection for prevention and treatment of severe pre–eclampsia and eclampsia ampicillin, gentamicin and metronidazole injections for treatment of maternal sepsis ampicillin, gentamicin, procaine benzylpenicillin, and ceftriaxone for neonatal sepsis and contraceptives including oral, emergency, injectable, and implant formulations. The medicines evaluated were on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines and some were listed as priority life–saving medicines for women and children by the WHO Department of Essential Medicines and Health Products. The two objectives of our study were: (1) to obtain a “snapshot” of the availability of oxytocin, ergometrine, and magnesium sulfate (MgSO 4), and (2) to use the Ishikawa “fishbone” diagram as a framework to describe the common barriers and facilitators contributing to use of these essential medicines. To investigate the availability and use of WHO–recommended life–saving medicines for women and children, WHO and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) conducted a descriptive study of essential medications for maternal, child, and reproductive health in seven low–resource countries between 2008 to 2010.

Even though the availability of essential medicines for maternal health is not well documented in many countries, recent data suggested that it is low in Africa and Asia. WHO has provided evidence–based recommendations for the essential interventions and medicines needed to improve maternal health and prevent these maternal complications. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that between 20, more than half of all maternal deaths resulted from haemorrhage (with postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) accounting for more than two thirds of cases), hypertensive disorders (pre–eclampsia and eclampsia), sepsis, and unsafe abortion. A lack of sufficient antenatal care during pregnancy and inadequate assistance from skilled health providers during delivery contribute to the high maternal mortality rate in developing countries.

Despite a 45% decrease in maternal mortality in the past two decades, the annual rate of decline has been far below the MDG 5 target. The fifth MDG aims to reduce maternal mortality worldwide by 75% between 19. In 2000, 189 member states of the United Nations adopted eight Millennium Development Goals (MDG). The higher number of pregnancies on average and a higher risk associated with each birth contribute to the higher adult lifetime risk of maternal death. Moreover, the probability that a 15–year–old woman will eventually die from a cause related to maternal health is much higher for women living in low income countries than for those who live in high income countries (1:160 vs 1:3700). An overwhelming 99% of these maternal deaths occur in low–resource settings, with Sub–Saharan Africa and Southern Asia accounting for 86% of overall global maternal mortality cases in 2013. Approximately 800 women die every day due to complications during pregnancy or childbirth.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)